By Ryan Fatica

The second of four articles from Unicorn Riot’s investigative series into the case of Marvin Haynes, who was sentenced to life in prison in 2006 at the age of 17 for a murder he says he didn’t commit. Almost a year after this article was originally published, Marvin Haynes was exonerated and released from prison. See the full series here.

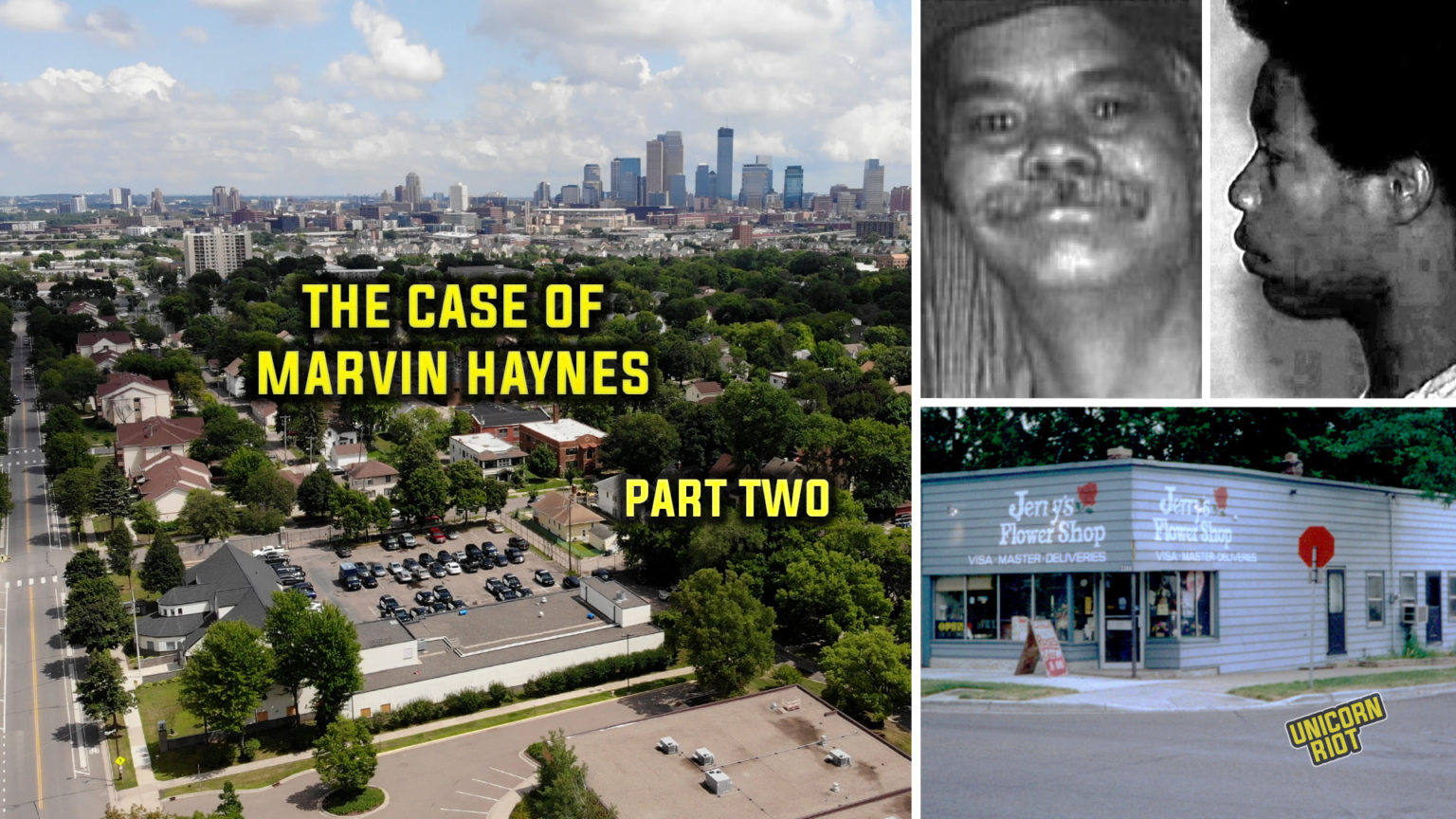

The story of Marvin Haynes is also the story of Harry Sherer — a 55-year-old man who lived a few blocks from his family’s flower shop who everyone called by his nickname, Randy. Most days, Randy walked to the shop to sit and talk to his brother and sister, to tidy up and smoke cigarettes, eat McMuffins, greet customers.

On May 16, 2004, someone shot Randy in the midst of a botched robbery attempt. According to his sister and sole witness to his killing, the shooter said he was looking for cash he thought was hidden in the flower shop. The neighborhood rumor, possibly founded on some truth, was that the shop’s owner was involved in high stakes gambling and maybe even ran gambling operations out of the shop’s back rooms.

In the end, the shooter left with nothing after firing a bullet that punctured Randy’s rib cage and entered his lung in two places — the aorta and the trachea — exiting the right side of his chest and quickly ending his life from loss of blood. One of the first officers on the scene wrote in his report that “blood from the victim extends from his body all the way back through [the] hallway.” Two discharged and deformed .38 caliber bullets that had entered and exited Randy’s body were recovered by police from the scene.

A subsequent autopsy revealed that Randy suffered from diabetes and severe coronary artery disease, a narrowing of the blood vessels that supply the heart with blood and oxygen. “If he had been a person who did not have these injuries to explain his death,” the medical examiner who performed the autopsy testified at trial, referring to the bullet wounds, “the amount of disease that he had to those vessels would be consistent with somebody dying suddenly and unexpectedly.”

Rev. Albert Gallmon Jr., Pastor of the Fellowship Ministry Baptist Church, remembers Randy from the neighborhood. “He was a dear soul,” Gallmon told Unicorn Riot. “I would go up there to order flowers or just walk around. He was a gentle soul, a very nice guy. He and I would just talk about anything in general from what I can remember and I was very, very disheartened when he was killed.”

Randy Sherer was a man nearing the end of a quiet life. He was loved by his family, who said he enjoyed watching the Timberwolves and playing golf, although he wasn’t very good at it. Marvin Haynes was a 16-year-old kid who liked to smoke a little weed, hang out with his friends, and try to dress nice and get girls. The two couldn’t have been more different. The only thing linking their fates was a neighborhood — Northside Minneapolis.

When Mannie Sherer got back from the war in the Pacific, he got a job in wholesale imports. He unpacked boxes of flowers and novelty items until, in 1948, he had saved enough to open his own wholesale flower shop.

He’d returned home to find Minneapolis in the midst of a post-war economic feeding frenzy. America had emerged from the Second World War a global player, pulled out of the Depression on the industries of war and centralized economic planning, which benefited a generation of young, white men like Mannie. The GI Bill and New Deal programs — a brand of democratic socialism the country would never again tolerate — infused the white working class with the capital they needed to start businesses, go to school, buy houses, and start families.

Sherer opened a flower shop at 802 NE Marshall St., on the east side of the Mississippi River, selling flowers at wholesale prices and undercutting the competition. When other florists were selling a dozen roses for $40, “we were probably selling them for $18 or $20,” said Mannie’s son Warren, shortly after his father’s death. “We were probably half the price of the bigger florists.”

In 1961, the elder Sherer moved the business across the river, opening a location at the corner of 33rd Avenue North and Lyndale Avenue North in the McKinley neighborhood on the Northside of Minneapolis. When one of his children, Jerry, was ready to go into business with him, they repainted the sign out front, calling the new store “Mannie’s and Jerry’s Flower Shop.”

What Mannie Sherer didn’t know when he moved his business just a few miles to the west, into Northside Minneapolis, was that he had settled in a neighborhood slated for abandonment and disinvestment by those in power.

The Northside of Minneapolis had long been a hub for marginalized people unwelcome elsewhere in the city. Beginning in the 1920s, racial housing covenants kept Black, Asian and sometimes Jewish people from owning land in most of the city, inscribing into deeds the restriction that the “premises shall not at any time be conveyed, mortgaged or leased to any person or persons of Chinese, Japanese, Moorish, Turkish, Negro, Mongolian or African blood or descent.” By the 1930s, the majority of deeds in the city of Minneapolis contained these racial housing covenants.

Leave a Reply