By Ryan Fatica

Monica had been locked up in Dekalb County Jail for five days when guards entered her pod and called out her name. She was being released.

Like always, the other women in the pod started clapping and cheering, happy to see anyone freed. Monica got up and went to her cell to start gathering her things, interrupted as she did by hugs and goodbyes from friends she’d made during her time there.

As she walked toward the cellblock door, one of her podmates stopped her for a hug. As she let Monica go, she looked her in the eyes and delivered a clear request: “Don’t forget us here.”

“I won’t,” she promised.

“That was a moment I will never forget,” said Monica, weeks later.

Monica, a forest defender who asked to be identified by an alias, was arrested on January 18, 2023, during a multi-jurisdictional raid on the Weelaunee Forest in DeKalb County, Georgia. Protesters had been camping and gathering in the forest for months in hopes of preventing the construction of a multi-million dollar police training facility, dubbed ‘Cop City’ by its opponents.

On the day Monica was arrested, Georgia State Troopers shot and killed Manuel Esteban Paez Terán, a 26-year-old forest defender who went by the name Tortuguita. Subsequent autopsy reports revealed that Terán’s body suffered 57 bullet wounds. During the same raid, Monica and seven others were arrested, charged with “criminal trespass” and “domestic terrorism,” and booked into the DeKalb County Jail.

Monica was granted bond and released after five days, but most of the women she lived with in the jail had been there much longer, some for over a year, awaiting trial. Other forest defenders served a month or more in the jail, including two, Victor Puertas and Luke Harper, who were arrested at a music festival in the Weelaunee Forest on March 5 and remain in custody nearly 12 weeks later. Another forest defender is still currently incarcerated in the Bartow County Jail.

Unicorn Riot spoke with and received testimony from more than a dozen people who were formerly incarcerated at the DeKalb County Jail, as well as family members of those held there and others familiar with conditions in the jail. Most of those interviewed requested that their names be withheld out of concern that sharing their stories could affect their ongoing legal cases. Most of those interviewed were ‘Stop Cop City’ activists, while others were held on unrelated charges.

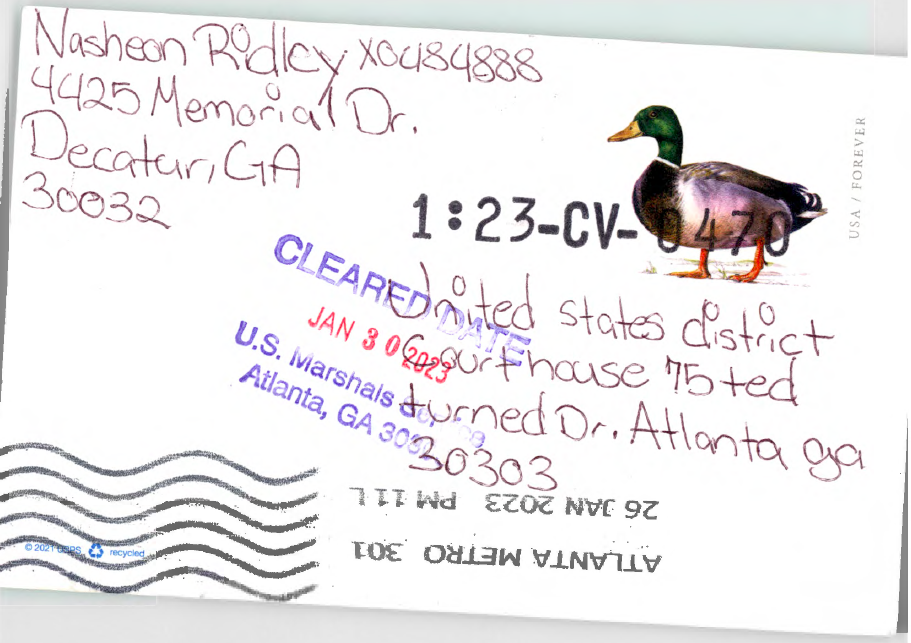

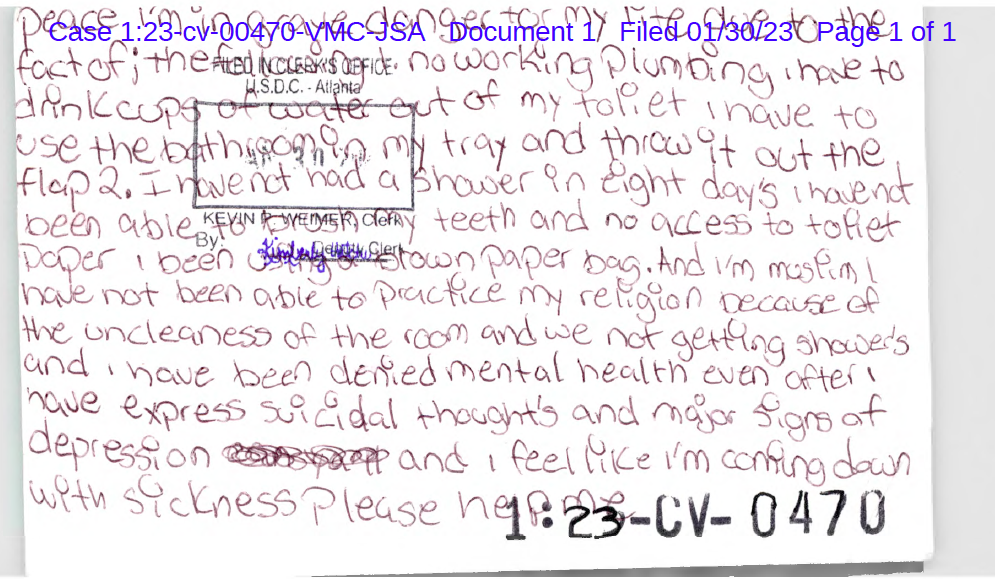

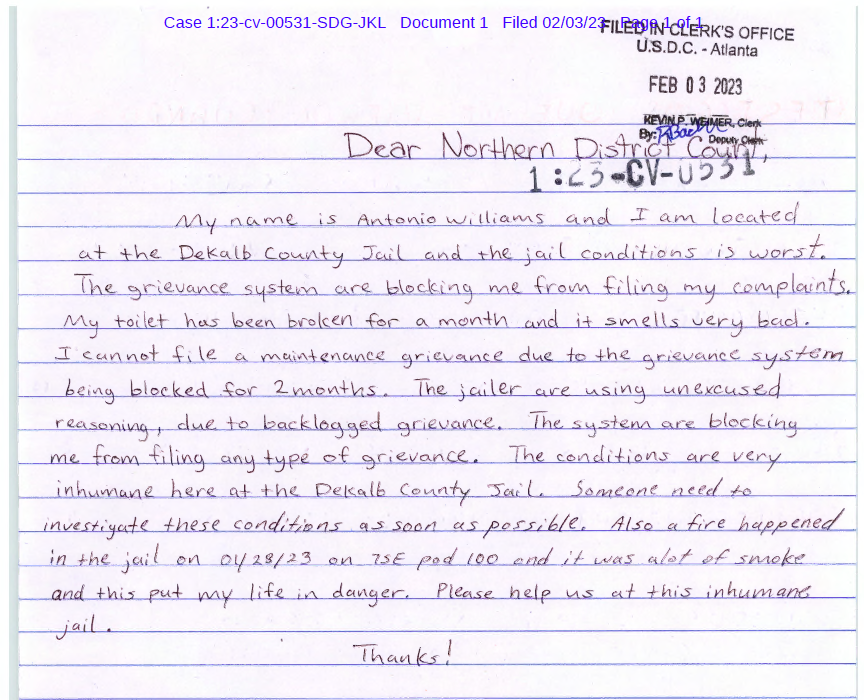

Unicorn Riot also reviewed dozens of pages of lawsuits filed by jail detainees raising civil rights complaints against the jail, the DeKalb County Sheriff, and its staff and contractors. Many of those lawsuits were filed pro se, without the help of an attorney, and handwritten on postcards purchased at the jail commissary. Many such lawsuits are dismissed on procedural grounds before lawyers for the Sheriff’s Office are even compelled to respond.

The stories they told each capture an existence, a moment of suffering, a tale of misfortune that would otherwise remain unseen. Taken together, they form a chronicle of inhumane, and often grotesque, conditions of confinement caused by a culture of neglect and apathy on the part of guards, contractors, and jail staff, often exacerbated by crumbling jail infrastructure.

In 2022, those conditions led to the deaths of nine people in the jail, a number that far exceeds the national average. Two of those deaths appear to be attributable to hypothermia after detainees were left in unheated cells in the winter. Others died by suicide or heart conditions after not receiving proper medical attention. Several of those who died in the jail had a history of struggles with mental illness.

“Nothing’s ever anybody’s job and it’s never nobody’s fault,” said Dulce, a woman who spent more than a year in the DeKalb County Jail who asked to be identified only by her nickname. “So it’s hard to get things done like they’re supposed to. Even with our food, they’d give it to us when they felt like it. We sat and watched our trays sitting in the hallway for hours. But because it wasn’t anybody’s job to do it, it wouldn’t get done. So we’re hungry just sitting there waiting for our food.”

Many of those we spoke with said they spent their time in the jail waking up at 3 or 4 a.m. to eat breakfast and then often going without food for 12 hours or longer. They talked about surviving on very few nutrients because they were often served undercooked or moldy food, much of it inedible. Some said they mopped their floors several times a day because the toilets or sewage pipes continuously seeped water and were never repaired, causing large puddles to form in their cells and pods.

[Header Photo by Tracie Will]

Leave a Reply